Forget about students spending one year in each grade, with the entire class learning the same skills at the same time. Districts from Alaska to Maine are taking a different route.

Instead of simply moving kids from one grade to the next as they get older, schools are grouping students by ability. Once they master a subject, they move up a level. This practice has been around for decades, but was generally used on a smaller scale, in individual grades, subjects or schools.

Now, in the latest effort to transform the bedraggled Kansas City, Mo. schools, the district is about to become what reform experts say is the largest one to try the approach. Starting this fall officials will begin switching 17,000 students to the new system to turnaround trailing schools and increase abysmal tests scores.

“The current system of public education in this country is not working” said Superintendent John Covington. “It’s an outdated, industrial, agrarian kind of model that lends itself to still allowing students to progress through school based on the amount of time they sit in a chair rather than whether or not they have truly mastered the competencies and skills.”

Here’s how the reform works:

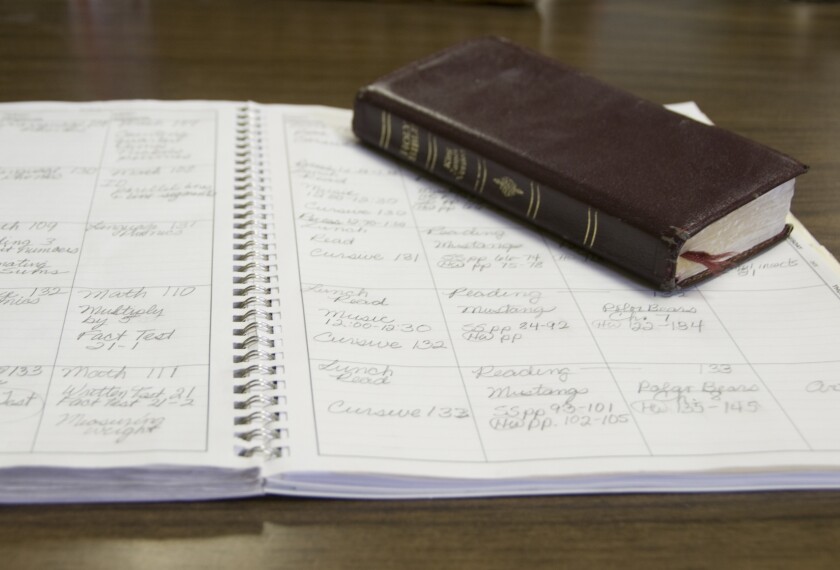

Students—often of varying ages—work at their own pace, meeting with teachers to decide what part of the curriculum to tackle. Teachers still instruct students as a group if it’s needed, but often students are working individually or in small groups on projects that are tailored to their skill level.

For instance, in a classroom learning about currency, one group could draw pictures of pennies and nickels. A student who has mastered that skill might use pretend money to practice making change.

Students who progress quickly can finish high school material early and move forward with college coursework. Alternatively, in some districts, high-schoolers who need extra time can stick around for another year.

Advocates say the approach cuts down on discipline problems because advanced students aren’t bored and struggling students aren’t frustrated.

But backers acknowledge implementation is tricky, and the change is so drastic it can take time to explain to parents, teachers and students. If the community isn’t sold on the effort, it will bomb, said Richard DeLorenzo, co-founder of the Re-Inventing Schools Coalition, which coaches schools on implementing the reform.

Kansas City officials hope the new system will help the district that’s been beset with failure. A $2 billion desegregation case failed to boost test scores or stem the exodus of students to the suburbs and private and charter schools. The district has lost half its students and will close about 40 percent of its schools by the fall to avoid bankruptcy.

Covington wants to start the system in five elementary schools in hopes of spreading it through the upper grades once the bugs are worked out.

“This system precludes us from labeling children failures,” Covington said. “It’s not that you’ve failed, it’s just that at this point you haven’t mastered the competencies yet and when you do, you will move to the next level.”

As it plans for the change, Kansas City teachers and administrators have visited and sought advice from a Denver area school district that uses the reform.

Adams County School District 50 has about 10,000 students this past school year its elementary and middle students made the shift. The reform will be phased into the high schools starting in the fall.

Count 11-year-old Alex Rodriguez as a convert to the new approach. He used to get bored after plowing through his assignments. He had to bring books from home or the library if he wanted a challenge because the ones at his old school were one or two grade levels too easy.

“I liked school,” he said. “But it was hard sitting there and doing nothing.”

His parents transferred the high achiever and his three younger siblings to the Denver area district after learning it was trying something new. His father, Richard Rodriguez, has been thrilled with the turnaround.

“I wish school was like this when I was growing up,” he said.

There also is growing interest in Maine, where six districts, with a combined 11,248 students, are transitioning to the reform, starting with staff training and community meetings and gradually changing what happens in classrooms.

“It is incredible what is happening in the classrooms in Maine that are trying it,” said Diana Doiron, who is overseeing the effort for the state’s education department.

Education officials in Kansas City, Maine and elsewhere said part of the allure is the success other districts have after making the switch.

Marzano Research Laboratory, an educational research and professional development firm, evaluated 2009 state test data for over 3,500 students from 15 school districts in Alaska, Colorado, and Florida. Researchers found that students who learned through the different approach were 2.5 times more likely to score at a level that shows they have a good grasp of the material on exams for reading, writing, and mathematics.

Greg Johnson, director of curriculum and instruction for the Bering Strait School District in Alaska, recalled that before the switch there were students who had been on honor roll throughout high school then failed a test the state requires for graduation.

Now, he said if students are on pace to pass a class like Algebra I, the likelihood of them passing the state exam covering that material is more than 90 percent. He’s proud of that accomplishment and said teachers love it.

“The most die-hard advocates for our system are our teachers because, especially the ones who were back with us before the change, they saw where things were then,” he said. “They see where things are now and they don’t want to go back.”