Early on a Wednesday morning last November, two high school juniors in uniform polo shirts stood in front of a large classroom at The Villages High School. As a shaft of central-Florida sunshine spread across the floor in a long rectangle, they presented a business plan for a mock pet-photography company called Top Dog.

“The residents here love their pets. They do anything for their animals. [Pets] are like their children,” Stephanie Park said, nervously fingering the seam of her khaki pants. “We have an advantage over other businesses in the area because there’s not much competition.”

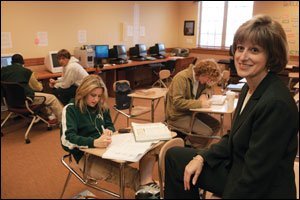

As the two students stood up front, shifting anxiously from foot to foot, business instructor Cindi Van Nostrand read through their proposal and asked questions. For a few moments, they discussed Top Dog’s potential clientele: the pets of older, difficult-to-please residents, seen by appointment only. “Really, your challenges would be retaining employees and meeting the needs of the customers,” she told them.

After Stephanie and her partner, Daniel Richards, finished explaining the company ownership structure and marketing strategy they’d devised, Van Nostrand gave them a loud ovation. “Good job,” the 45-year-old said from the back of the room. “Very good job.”

At Villages High, a unique creation of local development company The Villages Of Lake-Sumter Inc., the curriculum is serious business. Under its charter agreement with the Sumter County school district, the school must provide the academic basics, from algebra to English to physics. But the lessons are unapologetically business oriented. Stephanie and Daniel’s class, for example, might sound like Introduction to Marketing, but at VHS, it’s considered an art course.

After their presentation, the pair handed out business cards. “Top Dog Pet Photography,” they read. “Where Every Dog Is Top Dog.” Fine arts instructor Tina Jones, who cotaught the class with Van Nostrand, later pointed out an art angle to the project: the small, smiling-canine logo Daniel had created for the cards.

It’s not the way the arts are normally taught, but at this high school, which economic-development groups and education observers call rare, it’s literally business as usual.

Besides injecting business ideas and skills into core classes, the 400-student VHS requires most students to take an entrepreneurship class, and all must choose one of five majors: culinary arts, graphic arts, health occupations, art/ communication, or Advanced Placement. Math courses include segments on profit and loss statements, and in history class, students learn about the Federal Reserve’s control of inflation rates.

“We want the students to be engaged and feel that their school work is something real,” Van Nostrand said of the curriculum, “something that works out there in the world.”

Not everyone thinks that public schools should be dealing in price-point comparisons and flow charts, however.

“A lot of teaching business skills is just propaganda,” said David Gabbard, an education professor at East Carolina University. “It teaches students to be consumers, not thinkers.” Good public schools, he argued, prepare students to be future citizens, instilling in them a strong curiosity and desire for truth by teaching math, English, and the sciences.

Van Nostrand, who’d been working in the corporate sector for a couple of decades, and was teaching for the first time last fall, couldn’t disagree more. “The students,” she said, “are learning real-world skills and a level of critical thinking.”

There’s definitely some kind of thinking going on. Last year, all Villages schools received A’s under Florida’s school accountability system, and almost 70 percent of the senior class headed off to college. VHS also posted reading and math scores in the state’s top 10 percent at almost every grade level. Florida’s then-Governor Jeb Bush was impressed enough to deliver the school’s first commencement speech.

Students appear to both enjoy and thrive in the district, which began with an elementary school in 1999 and has grown to include an early childhood center, as well as a middle and high school. “[There’s] definitely a really strong community feeling [at VHS],” said Whitney Windham, who graduated last year and now attends the University of Central Florida in Orlando. Academically, she added, “The Villages really prepared me in my studying habits. I feel like UCF has been a breeze so far.” Windham also credits the school for inspiring her interest in business. In her culinary arts classes, she learned the back-office skills of being a restaurateur and plans to major in business.

If studies paid for by business boosters can be believed, teaching entrepreneurship engages students and enhances learning. Schools such as The Villages High School in central Florida incorporate business ideas and practices into their curricula, but not all K-12 students are well versed in how capitalism operates.

The National Council on Economic Education, a New York City-based nonprofit, reports, for example, that “a majority of high school students do not understand basic concepts in economics.” This, the NCEE argues, “has implications for young people’s ability to manage their personal finances and to function well in today’s global economy.”

Those who’d like to know how to include business in the curriculum might start by checking out the NCEE Web site at www.ncee.net. Lesson plans and other resources on economics and personal finance are available for free.

The National Foundation for Teaching Entrepreneurship (http://www.nfte.com) has trained more than 3,700 teachers to help students learn how to start their own businesses. Its program focuses on low-income areas, and commissioned studies by the Harvard Graduate School of Education and other institutions found that, after students took classes with NFTE-certified teachers, their interest in attending college increased by nearly one-third.

Like Villages High, the Cristo Rey Network schools (www.cristoreynetwork.org) infuse their curriculum with entrepreneurial knowledge, only they add a religious bent. Students who attend the national network’s 12 Catholic high schools typically spend one day a week in a work-study program for every four days in the classroom, and what students learn on the job gets discussed in class.

And, finally, for those who think that business is all business, a new Web site tries to show that entrepreneurship can be fun, too. Created by Disney Online and the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, Hot Shot Business (www.hotshotbusiness.com) offers kids the chance to open virtual businesses. While they run a simulated candy factory or pet spa, for example, they have to decide about production and sales, and they face the same kinds of challenges as real-life company owners: If profits are slow, they even have to lay off workers.

Prospective students’ families are also drawn to the school. Enrollment has grown, most grade levels have a waiting list, and an expansion project to add about 50 classrooms to the system is under way, said director of education Randy McDaniel.

But Villages is no ordinary charter school system, and the pool of parents wanting to enroll their children isn’t ordinary either. Under the aegis of Florida’s 1999 “Charter School in the Workplace” law, Villages schools do not draw students according to geographic boundaries. They accept only those whose parents work directly or indirectly for The Villages Of Lake-Sumter Inc.—the company that developed the 23,000-acre retirement community of houses, pools, shuffleboard courts, polo grounds, and more than two dozen golf courses also known as The Villages.

Even if they live 20 to 30 miles away, parents employed by the company as executives or by local supermarkets on Villages property as security guards can enroll their kids at the schools, located within the 62,000-resident development. Parents who have no affiliation to The Villages but live within spitting distance of the schools are out of luck.

“My goal was to have my kid go here,” remembered Bernadette Scanlin, who took a job as the high school’s receptionist when she moved to the area three years ago. Now a substitute teacher, Scanlin said she turned down better jobs in other businesses in favor of VHS’s tight-knit environment and high achievement scores.

Indeed, most parents view the school as an employment perk, much like good health care and solid pensions. “This helps The Villages attract great employees,” said Patrick Leahy, who has three kids at VHS and directs instruction for The Villages Golf Academy. “It helped bring us here [from Atlanta].”

The use of public education dollars to lure prospective company employees hasn’t played as well outside the community, however.

“Public funds are being spent to benefit a corporation—that’s perverse,” commented Georgia State University education professor Deron Boyles, after being told about the operation. “We should be taxing the companies and using the money to help all the schools in the area.”

Critics worry that The Villages’ kind of setup creates a two-tiered system, in which company schools provide better instruction than traditional ones, and keep out unwanted students. The latter issue boiled over in 2005, when victims of Hurricane Katrina stayed with relatives in The Villages, and a number of displaced families tried to get their kids into VHS. According to The Daily Commercial, a local newspaper, all were denied admission. “You’re telling me they can’t bring in a few more extra chairs?” one grandmother told the paper. “What happened to [President] Bush’s speech telling people to open their hearts and their schools?”

The high school was opened as a Red Cross shelter for displaced residents in early February after tornadoes ripped through central Florida. As part of their 150-hour community-service requirement, VHS students also helped clean up damage to Villages and nearby property, just as they did for two weeks in Mississippi after Hurricane Katrina.

As for the shut-out Gulf Coast students in 2005, McDaniel explained that the admissions rules were set up by the state and that neither the developer nor the schools are to blame for the restrictions. “We’re just following the charter,” he noted.

More important, he added, Villages Charter Schools are operated as a not-for-profit entity, so no one’s making money directly off the enterprise. In fact, he said, although the system receives roughly $9 million in public funds each year, the developer kicks in for facilities maintenance and operation. “We want to give back to the community,” McDaniel explained.

It was just after lunch at VHS, and a dozen teenagers were spilling into Van Nostrand’s class on entrepreneurship—a graduation requirement for most students, and a subject with which she’s had professional experience. Before working in finance and accounting for various health care companies for almost 20 years, the former New Jersey resident helped operate a limousine service.

Because of a scheduling conflict that day, she was meeting her students in the high school’s health-occupations room, adorned with medical paraphernalia and a prone CPR mannequin she was doing her best to ignore. Her giggling, gossiping students—all in the green hospital scrubs required for health majors—looked right at home.

“The students are wonderful,” Van Nostrand would say later, adding that she was truly enjoying her new career. But in class, dressed in her black business suit, and with her brown hair as tightly coiffed as a TV news anchor’s, she still looked more like a businesswoman than your typical educator.

According to Van Nostrand, the class focused on career-building skills, entrepreneurial concepts, and economic principles. That day, however, they were studying marketing techniques. Van Nostrand divided the students into two groups. One was told to search online for the best prices for an iPod nano, while the other was charged with hunting down deals for a digital camera, the Kodak EasyShare C530. Van Nostrand helped the students get started on the room’s top-of-the-line desktop PCs.

As the teenagers searched the Web, she explained that the goal of the lesson was to figure out how companies set up price structures for products. After guiding the students through retailers’ Web sites, Van Nostrand gathered them together to present their findings. The iPod group had found prices clustered around $200, while the Kodak kids discovered a wide range: $80 to $200.

“Apple has a consistent image, consistent pricing—they have one way they want their product to be seen,” she explained to the students. “Kodak allows for differences.”

As the bell rang, Van Nostrand reminded them about the required reading: Spencer Johnson’s Who Moved My Cheese?An Amazing Way to Deal With Change in Your Work and in Your Life, a motivational book aimed at businesspeople. Finish it before the deadline, she added, and I’ll give you five extra points for Accelerated Reader. The program, used to evaluate reading comprehension, isn’t the only point system at the school. Students can also earn behavioral points—called “buffalo chips” after the school’s buffalo mascot—for good conduct, and have them deducted for late homework.

“It’s like in the business world—you have reward systems,” Van Nostrand explained after the kids left. “This encourages the students to strive, to do better.”

Setting aside the question of how such lessons contribute to students’ intellectual development, some critics question their ability to prepare students for a business career—if, in fact, any curriculum can.

“I don’t know what universal work skills really are, except to show up on time,” Georgia State professor Boyles said. “And kids already learn that with the school bell.” He believes that schools should equip students with a solid basic education and allow companies to teach work skills after students graduate. Why waste time learning how to operate a deep-dish pizza oven, as VHS culinary arts students do?

“Business is contextual work,” he added. “You learn it on the job.”

Some also complain that the school is using public funds to train students as future employees of The Villages. “It’s a private school for the employees,” says Rose Harvey, who moved to the area almost 20 years ago from Mississippi. “We’re paying [extra] for those students to gain a specialty … and then go work for the company.”

Certainly, the school’s majors match the regions’ employment needs. Culinary arts graduates could work in local restaurants, and the grads who specialized in health occupations could help take care of the aging Villages population. And for the school’s administration, that’s largely the idea.

“It’s all about relevancy,” said McDaniel. But, he argued, the school is not about teaching the business of The Villages. “We don’t teach a construction class,” he pointed out. “We want to teach the core concepts with every [student] taking business.”

In fact, Villages High is intensifying its entrepreneurial-education focus. For the first time this school year, each senior must write a detailed 25- to 30-page business plan, using material from across the curriculum. The school’s English teachers, for instance, help those struggling to put their ideas into words, while the math instructors oversee work on spreadsheets and charts.

The project, according to school principal Michael Kelly, is a further effort to engage students and show them the material’s real-world applicability. The business plans, he noted, will be graded not only by teachers, but by a panel of local businesspeople.

“The idea,” Van Nostrand said, “is to make the plans as realistic as possible.”

But she won’t be in the classroom to see the results. Over the holiday break, she decided to return to the health care profession as a finance expert.

Kelly described her as a great teacher, and sounded disappointed to see her go, but was realistic. “This is what they do; they’re businesspeople,” the principal said, referring to those hired to be business instructors at VHS.

As for Van Nostrand, now finance and accounting manager at Hospice of Marion County Inc., she says, “I’ll miss the students. It was hard leaving. But I’m afraid that if I don’t maintain my accounting skills, I’ll forget them.” She plans to stay connected to Villages High by hosting seminars or serving as an outside speaker. The details have yet to be worked out with Kelly, who confirms the possible arrangement.

Meantime, Van Nostrand has been thinking about entrepreneurial opportunities for her former students, once they’ve received their diplomas. She believes there’s a need in The Villages for same-day dry cleaners, as well as a good Italian deli that stocks high-quality cheeses and pastries.

“I see a lot of business opportunities here,” she says, “for the people who want to actually start a business.”