It’s November 10, a week after George W. Bush was reelected, and occupation forces are trying to flush insurgents out of one of Iraq’s most dangerous cities. Alluding to the day’s headlines, Paul Watkins tells his history class that “air power is an integral part of any military assault. The attack on Fallujah, which began about 36 hours ago, began with an airstrike.” But now he wants to take the teenage students back 90 years, to when planes were far less deadly weapons. With their open cockpits, in which rifles were stowed for self-defense, early World War I aircraft served primarily as reconnaissance tools. Only occasionally did pilots take potshots at the enemy.

Watkins stands at the front of a small, white-walled classroom. Behind him are three sets of maps, the middle one flecked with red starbursts marking battles from the Great War. His 14 students—wearing bobby-soxer, peacenik, and leisure outfits for homecoming week’s “Decades Day”—sit at long tables. On the walls are prints of propaganda posters, all with the same theme: “Loose Talk Can Cost Lives.” There’s also a tattered Union Jack, a Watkins family heirloom. The sign next to it reads “This Flag Flew Above a British Regimental Command Post on the Somme 1916-17.”

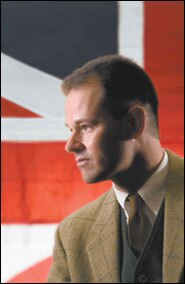

Appropriately enough, Watkins looks like a figure from another era. Before the 9 a.m. class began, as young men and women mingled in the wood-paneled lobby of Annenberg Hall, I spotted him barreling across the Peddie School quad, a satchel slung across his tan tweed jacket. He’s 6 feet 2 inches tall, weighs 195 pounds, and once played rugby, so I almost expected him to flatten a few students. But, after bounding up the front steps, he deftly navigated the human obstacle course without stepping on a single toe. Watkins then blurted “good morning” and led me downstairs.

Now, in green vest and matching tie, his sleeves rolled up, he reads to the class from an old newspaper interview with Lieutenant W.R. Read of the Royal Flying Corps. In August 1914, after Read and his “observer,” Jackson, spotted a German plane, Jackson insisted they give chase. Read, however, reminded him that they’d finished their reconnaissance mission, saying, “Better get home with your report.”

Jackson, not easily swayed, repeated: “I think we ought to go for him, Old Boy.”

“Oh, all right,” Read replied.

It’s worth mentioning that although Watkins was born in the United States, the 40-year-old spent his formative years in English boarding schools, so the Oxbridge accent he’s using to narrate the account is spot-on. And as a bit player in Peddie’s Shakespeare productions, he has a flair for the dramatic—fitting, since the account continues with Read recalling his pursuit of the German aircraft as Jackson fired away with a hunting rifle. After running out of ammo, Jackson asked Read if he had a revolver. Watkins continues with the back-and-forth:

“I, feeling rather sick of the proceedings, said, ‘Yes, but I haven’t got any bullets.’

“ ‘Give it to me anyway, Old Boy, and this time, fly past him as close as you can.’

“I carried out the instructions, and, to my amazement, as soon as we got opposite the German machine, Jackson, with my Army-issue revolver grasped by the barrel, threw it at the German’s propeller.

“Of course, we missed him then, and, with our honor satisfied, we returned to home.”

Watkins waits a few beats, then says, “These people were obviously completely mad,” which elicits laughter from the class. “But,” he adds, “I think you had to be mad in those days to take on such an outlandish invention as the airplane.”

These two sentences say a lot about Watkins. The first implies that like his students, he considers the risks the pilots took almost incomprehensible. But the second hints at his capacity for empathy, which, combined with exhaustive field research, has served him well as a writer. The author of eight novels and two memoirs, Watkins began his literary career at 23, with Night Over Day Over Night, a novel about a young German soldier fighting in the Battle of the Bulge, which earned him a Booker Prize nomination in England. His latest work of fiction, Thunder God: A Viking Quest, is set in 10th century Norway. Watkins’ vivid rendering of history is one reason why Hollywood has shown interest in many of his books.

What few in the filmmaking and publishing industries know, however, is that Watkins is also a veteran educator. This is his 15th year at Peddie, where, as writer in residence, he’s discovered that his passion for telling stories and taking readers places they’ve never been fuels his teaching, as well. He’s also learned that any good educator can become “indecently proficient” if he or she isn’t careful. So, enabled by the flexibility his post at Peddie provides, he’s varied not only his methodology but also the subjects he’s taught there—everything from fiction writing to World War I.

But Watkins is hardly the sole beneficiary of this arrangement. His students see in him someone who clung tightly to—and never let go of—the kinds of youthful aspirations too often dismissed as unrealistic. “He really has an ability to empathize with his high school students,” says Gwyneth Connell, a Peddie alumna who now teaches history herself. “He knows how important this stuff is to them.”

‘Wake up, Christian,’ Watkins says to one of the students in his World War I class. “Keep your feet down; it’ll help you to stay awake.”

Even in a half-credit elective course at a private school that costs boarders roughly $30,000 a year, one or two students will at least act like they’re bored. But Watkins, continuing his lesson on “War in the Sky,” rarely misses a beat, even responding to inane questions as if they’re part of the lesson. After one student asks, for example, why World War I pilots didn’t just load their planes with explosives and crash them into enemy lines, as the Japanese did to ships in World War II, Watkins flashes a hint of incredulity, then says, “The Japanese did do it, but it was a symptom of their desperation, not of their discipline.”

I’m reminded here of something Peter Kraft, chairman of Peddie’s history department, told me before I arrived on the sylvan 230-acre campus in central New Jersey. Although Watkins allows for give-and-take, he’s a skilled lecturer with “a deep, lyrical sense of the language,” Kraft said. “And the way he chooses his words is captivating.” In fact, everyone I’ve talked to—colleagues and students, both former and current—has boiled down Watkins’ classroom performance to one trait best articulated by the department head himself: “He’s a brilliant storyteller.”

I first recognized this same trait in winter 1990, a few months after Watkins had joined the Peddie staff, when I was an arts-and-entertainment reporter for a New Jersey newspaper. His third novel, In the Blue Light of African Dreams, about a French Foreign Legionnaire attempting the first trans-Atlantic flight, had just been published. Watkins is prolific, putting out a book every 18 months, so I ended up writing a few pieces on his work during the next decade. But until today, I’d never seen him teach.

“A good old chap,” is how 17-year-old Alli Blum, a World War I student, describes her teacher. “He’s American, but he speaks and dresses like he’s British. And he’s so humble. That’s one of the first adjectives that comes to mind because he’s always asking us, ‘Am I doing everything OK? Is there anything I can do—more of this, less of that?’ ”

Peddie alumna Elizabeth Maki, a former fiction-writing student who’s now a sophomore at Oberlin College in Ohio, concurs, saying, “He’s the most gentle teacher I think I’ve ever had.”

In 1990, however, I could only guess at his classroom talents. He was certainly generous in answering questions on subjects I was ignorant of—early air travel, for example, and Morocco, where he’d done research for Blue Light. But I was also a bit awe-struck. We were both 26, and I was just beginning a career in journalism while he’d already published three novels and traveled much of the globe. And his book Calm at Sunset, Calm at Dawn, a fictionalized account of his work on fishing boats to help pay his way through Yale University, had won Britain’s Encore Prize, for best second novel.

I wasn’t the only envious one. Patrick Clements, an English teacher at Peddie since 1976, remembers when Watkins and his then-girlfriend, Cathy Robohm, arrived as teachers in fall 1989. Cath, as she’s known on campus, was, and still is, striking—tall, lithe, blond, and gray-eyed. Although Peddie was the couple’s first experience teaching, they showed promise early on, according to Clements, who adds, “Two or three of us [on the staff], we said, ‘This isn’t fair. They’re gorgeous, and they’re nice,and they’re really good.’ ”

At the time, though, Peddie seemed just a way station. Before accepting her job, “I really had never considered being a teacher,” Cath says today. “I mean, neither of us had—ever.” Which makes sense; as a recent art school graduate, she planned to make a career out of her paintings and mixed media works, many of which hang in the house the Watkinses, married for 14 years, now share with their kids, Emma, 8, and Oliver, 6. And Paul, back then, was enjoying a newfound literary career, complete with a Hemingwayesque image.

So it wasn’t easy for anyone, especially Watkins, to know he actually needed the teaching job—or that he and Cath would become an integral part of the Peddie community.

It’s November 9, and Watkins and I are seated at a window booth in the spacious Americana Diner, which overlooks U.S. Highway 130 in Hightstown, New Jersey. Watkins, who no longer resembles the brooding, model-like figure once splashed across hisbook jackets, is nevertheless still handsome—with brown eyes, high cheekbones, and thinning hair. He tells me, over a melted Reuben and french fries, that after 9/11, Hightstown became a home base for self-exiled New Yorkers. Indeed, its Main Street, lined with mom-and-pop stores and Victorian-style houses, is an idyllic vision of small-town America. But when I was growing up, not far from here, Hightstown was mostly blue-collar; I always thought it odd that smack-dab in the middle of town was Peddie, looking like a country club with its gates and lake and red-brick buildings.

Peddie and Hightstown actually go way back. Founded in 1864, the school traditionally served boarders and day students bound primarily for second- and third-tier colleges. This dynamic began to change, however, after Peddie alumnus Walter Annenberg, the late media mogul and philanthropist, gave his alma mater $100 million in 1993. Although most of the endowment goes toward financial aid, it has also freed up funds for other projects, including renovated living quarters and sports facilities as well as laptops given to the 500-plus students from 18 states and more than 20 countries.

Thanks to the Annenberg gift, 42 percent of the kids in grades 9 through 12 (plus post-graduate students) receive from $100 to a full ride, according to headmaster John Green. And while Peddie has been able to make improvements that draw Ivy-bound students, he insists that “caring mentors working with curious kids” remain the heart of the school. The mentors’ salaries are consistent with those in the public sector—ranging from $28,000 to $75,000 per year, Green says. Throw in the perks—free food and housing, a nonexistent commute, access to the gym, et cetera—and you have a pretty good setup.

But you’re also on call 24/7, living among adolescents who are far from home. “The parent who sends their kid here is looking to us as the adults to play that role, sort of surrogate parent in their absence,” Cath says. So it makes sense that anyone who’s stayed for 15 years, as the Watkinses have, must have found something remarkable in the setting. Paul, who also taught a fiction-writing class at the nearby Lawrenceville School for nine years and who has conducted workshops at other prep schools, says one reason he’s still at Peddie is that “it’s quite singular. I find that it’s a very balanced atmosphere.”

Before arriving at Peddie, both he and Cath led peripatetic lives. They met as students at Yale, graduated in 1986, then went to Syracuse University, where Paul enrolled in the graduate creative-writing program and Cath, unsure of making a living off art, earned a master’s degree in journalism. At 18, Watkins had begun research for Night Over Day in the Ardennes forest, the setting of the Battle of the Bulge, and he arrived at Syracuse with a draft already written. After one of his teachers, Tobias Wolff (a writer best known for This Boy’s Life), read it, Wolff showed it to his agent, who quickly sold it to a major publisher. So Watkins decided not to finish the program; his career had already begun.

It was going full steam in 1988, when the couple moved to Baltimore, where Cath took classes at the Maryland Institute College of Art. But Watkins, who’d finished Calm at Sunset and was writing Blue Light, knew something was amiss. As alluring as a nomadic existence seemed in his teens, he realized after spending eight weeks in Morocco without Cath that fiction alone was insufficient. “I was literally cutting off the resource that would fuel the writing, i.e., the world outside,” Watkins recalls, slicing into his Reuben with a knife. “I was completely monastic about it.” He felt, he adds, “like Howard Hughes without the money.”

Watkins has garnered critical praise throughout his career, but his books, which aren’t easy to categorize (literary historical adventure novels?), sell only modestly. These days, his writing is a reliable source of supplemental income via advances, workshop fees, and movie options (although, thus far, only Calm at Sunset has been produced for television). But in 1989, Paul and Cath needed full-time gigs. So, after finishing art school, she looked into independent schools, which value expertise in specific subjects. An interview at Peddie quickly landed Cath a job in its then-small art department (which she’s since helped expand considerably) and the chance to mention Paul. It turned out that the woman doing the hiring had recently heard Watkins in a National Public Radio interview; so funding was quickly found for a writer-in-residence post, which demanded that he teach just one fiction-writing course per term, allowing him ample time for his own literary work.

The first class, Watkins recalls, was a near disaster. Just minutes prior, he had visited the men’s room, where the flush of an overzealous urinal soaked his pants. “It looked like my bladder had exploded,” he recalls, laughing. So, with his jacket buttoned tightly, he slipped behind a desk and stayed seated for the entire three-hour period.

This is the kind of story that helps shatter the Serious Writer image that’s been presented in the press. Plus, there are the appearances in student Shakespeare productions—usually in bumbling comic roles—and the campus readings Watkins gives from Stand Before Your God, his memoir of the awkward adolescent years he spent in English boarding schools. “First impression, he comes across as rather eccentric,” admits Bill McMann, chairman of Peddie’s English department. “But there’s great warmth.”

And, very often, humor, as this passage from his latest memoir, The Fellowship of Ghosts: A Journey Through the Mountains of Norway, attests:

I had been searching [the Internet] for some information on the Norwegian explorer Amundsen when I noticed a site called “Norwegian Celebrities.” Realizing that I did not know of many Norwegian celebrities, I clicked on it. The screen exploded into a maze of female body parts. Web site after Web site popped into view, as if someone were fanning a deck of naked-lady playing cards in front of my face. I should add that this was on a school computer in the faculty lounge of the Peddie campus, where I teach one class a week. Terrified that someone would look over my shoulder, I began to click them off, but as soon as I got rid of one, another appeared. At no point did I see anything to do with Norway. It seemed a very long time before the last of these sites disappeared, after which I felt obliged to turn myself in to the school tech department before Peddie security decided to escort me from the premises. Several sarcastic comments later, I was released from the beeping, buzzing, plastic-smelling tech room and added the episode to my far-from-empty file of embarrassing moments as a teacher.

The personal anecdote is a cornerstone of Watkins’ writing and pedagogy. In the World War I class, for example, after explaining how advances in weapons technology turned airplanes into “killing machines,” he insists that not just anyone could fly them. The best pilots—including Manfred von Richthofen, aka the Red Baron—seemed organically connected to their machines.

“Has anyone ever been in a biplane?” Watkins asks.

The students shake their heads no.

Years ago, he tells them, he spotted one while driving; it was sitting next to a sign that said “rides.” He pulled over, paid $20, then climbed into the front seat of a “somewhat rickety” plane. The pilot, sitting behind him, offered no reassurances, so Watkins considered bailing. Then an assistant turned the propeller.

“All of a sudden, it feels like your ribs are going to be shaken apart,” Watkins says. “The whole machine starts vibrating. The prop turns into this grey blur in front of you. Smoke coughs out of the side of the engine. Everything seems incredibly primitive.”

He worried that the grass runway wouldn’t be long enough, but with a rev of the engine, the plane lurched forward and was soon airborne. As cars, trees, and cattle shrank from view, the plane worked its way up to 100 miles per hour with nothing but a wind screen and a pair of goggles separating Watkins from the roaring slipstream.

“The idea of feeling that much more attached to the plane is something that is almost unrecreatable in the age of modern air,” he tells the students. “What I’m trying to get across is, ... despite the fact that people were getting shot down [during World War I], there was an extraordinary beauty—not only to the machines but to the way that they were being flown.”

The descriptive, firsthand account is not just a storytelling technique with Watkins; it’s a byproduct of his evolution as an educator. He realized shortly after arriving at Peddie that he enjoyed teaching. But a few years later, he reached a “level of proficiency,” he says, that any self-aware educator recognizes as “coasting.” So, as a personal challenge, he began changing the format and content of his fiction-writing course. And when the opportunity arose several years ago to teach World War II history, he took it. He added World War I, another passion, to his repertoire this year.

“The best teachers I’ve ever had have been people who had such a laserlike focus on their subject that they no longer seemed to care whether the rest of the world was listening,” Watkins says. “They had this urgency to talk about this thing. ... It’s the same with fiction. And this is where I started to realize that these things [in my life] overlap, in a very healthy way.

“That’s the first thing I tell fiction students: ‘For god’s sake, don’t write what you think I want to read. Write what you would read’—because I would rather have an urgently written story than something that was proficient.”

This urgency is most evident in his relationships with students. McMann, the English department chairman, says the end-of-term evaluations of Watkins are always “glowing” and adds, “I think he’s really just affirming when he’s dealing with kids. Even when [student work is] god-awful, he doesn’t say it’s god-awful.”

He does, however, demand discipline. Rob Kunzig, a freshman at Kenyon College in Ohio, remembers hearing about Watkins’ experiences with bottom-line publishers. So romantic notions of being an “artist,” he recalls, were secondary to making sure seven pages were written each week for his fiction-writing class. With Watkins, Kunzig says, “you’d better live up to your end of the bargain. You’d better do the work.”

Some World War I students have taken Watkins’ fiction-writing and World War II classes already. Where he goes, they seem to follow—mostly, senior Zev Reuter says, because he “really worries about whether you like [the material] or not.” The material is sometimes found outside the classroom, where Watkins has students dig trenches to get a feel for military grunt work. Reuter and Alli Blum say that, for World War II, they field-tested authentic Russian, German, and French camouflage uniforms.

“We got to run around” in the woods, Zev says.

“Yeah,” Alli adds, “it was neat.”

These kids are getting a taste of the research Watkins does for each book—whether it’s set in civil-war-era Ireland (The Promise of Light) or Nazi-occupied Paris (The Forger). With history, especially, their teacher provides what he calls “the microcosmic view.”

“What’s so interesting about Mr. Watkins,” says World War I student Liz Vlock, “is he’s devoted chunks of his life to studying only this war. He wasn’t there, but he has this firsthand perspective of being able to go [to battlefields] and be able to tell us what the forest looks like that they fought in and how the troops were feeling when they were there.”

On the second floor of Watkins’ house is his high-ceilinged study, where half a dozen windows overlook a leaf-strewn section of the Peddie quad. On one of two antique desks, next to the Penguin Dictionary of Surnames (with “Kilroy is here” scribbled across the cover), sits an Apple iBook. An unedited manuscript for The Ice Soldier, about a mountain-climbing World War II vet who happens to be a boarding school teacher, is on the floor; it’s due to be published in 2006.

Also in the works is a memoir about Watkins’ literary career, a sequel to Stand Before Your God, which was published in 1993 and begins with the line “I swear I thought I was going to a party.” At the age of 7, dressed in a suit and tie, Paul was taken to what appeared to be a cocktail reception. His father then said goodbye, neglecting to tell his firstborn that he’d be staying at the Dragon School indefinitely—while his family returned home to Narragansett, Rhode Island.

As cruel as this setup may sound, Stand is a testament to Watkins’ storytelling skills. Told from his younger self’s point of view, it’s an amusing, adventurous, and harrowing account of an 11-year experience that ends with his graduation from Eton, England’s most prestigious boarding school, whose alumni include prime ministers and royalty. Exactly why his Welsh-born parents sent him—and, later, his brother, Clive—abroad at such a young age is best explained by Watkins himself. In Stand, he writes:

My father didn’t go to Eton. He quit school at 17 and went to work in a factory that made airplane engines. He hated it so much, he went back to school and on to university at Leicester, where he met my mother. He became a geophysicist, and they moved to Canada right after they got married. ... Sending me to the Dragon School and then Eton was a way of making sure that my brother and I didn’t end up back in the kind of situation in which my father had grown up.

The 6-foot-6-inch, 250-pound Norman Watkins is an almost mythical figure in the memoir, an ultra-disciplined, self-reliant man who would nevertheless succumb to cancer at age 43, when Paul was 13. A rootless and fatherless existence, male camaraderie and rivalry, getting by on ingenuity and brute strength—these themes occupy many of Watkins’ books. And in Stand, it’s evident just how formative the Dragon and Eton experiences were. Both schools were steeped in war history. So it’s no surprise that an adolescent Paul, who’d begun dabbling in writing, should discover what he calls “the power of storytelling” after watching the film Zulu, a fictionalized account of how, in 1879, 130 Welsh soldiers defended a British colonial stronghold against 4,000 Africans. From that moment, Watkins was “set loose of the bone box of my skull,” he writes, and he dedicated himself to telling his own stories set in the past.

In Watkins’ class, the past is most present on days like this one—November 11, otherwise known as Veterans Day. It’s a day of remembrance prompted by World War I, which saw casualties numbering in the millions and ended in Europe, as Watkins tells his students, “on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918.” But now he wants to do them a favor—especially Liz Vlock, who earlier this term requested a respite from death and devastation. First he tells a few jokes from the era. Then he shows a clip from The Dawn Patrol, in which Errol Flynn, playing a British World War I pilot, storms a German airfield, decimating most of it with bombs he drops from the cockpit. Whooping it up, Flynn seems to be having great fun even after his plane is shot down, forcing him to escape on the wing of another British aircraft.

This popular 1938 film, Watkins tells his students, did for the World War II generation what John Wayne’s Sands of Iwo Jima would do for the next generation—glorified the lives of fighting men.

And, in fact, World War I pilots did have fun, he adds. Their job was so dangerous, they were given carte blanche between missions. “British officers, educated at Oxford and Cambridge,” he says, “would be lying in these vast beds, drinking champagne from the cellars of French barons, reading incredibly rare illuminated manuscripts—whereas their brothers out there in the trenches are eating bully beef and getting shot at. So it’s this life of extraordinary luxury. They have music, they have the company of women, they have wine—compare that to the misery of the trenches.”

The pilots weren’t, however, expected to live long—a few weeks, on average. And during that time, they’d more than likely witness the maiming and/or killing of friends and colleagues.

This brings to mind something Watkins experienced when he was 19, working one summer day with a fishing crew. He tells the class that as the boat’s two dredges scraped the ocean floor, he was below decks, storing bags of scallops in ice. It was cool in the hold, so he didn’t mind waiting for the dredges, weighing a ton each, to be brought on deck and secured. Soon, he heard them thundering above. He waited a few seconds, then climbed the ladder.

“I remember thinking, Where’s the sky?” recalls Watkins, who was suddenly back in the hold on hands and knees, spitting out sand. The water sluicing between the ice piles was pink, and sure enough, his T-shirt was drenched with blood. But there were no wounds on his torso. What he found instead was a hole in his right cheek. He realized he’d been spitting out teeth.

Later, after piecing together eyewitness accounts, Watkins learned that only one dredge had been brought on board when he emerged from the hold. The other, just then swinging across the deck, dislocated his jaw and sheared off three back teeth. Falling face-first into the hold, he relocated his jaw and broke two more teeth. The injuries were painful, but they weren’t life-threatening, and the boat was 200 miles from shore. So for the next week, Watkins subsisted on cake frosting and grits. A root canal, a handful of crowns, and thousands of dollars later, he had a full set of teeth. But the incident haunted his dreams for months.

“Why am I telling you all this?” Watkins asks his students. “Because you will become aware, as soldiers become aware, of the appalling fragility of flesh.”

Referring to the outline he distributed earlier, he adds, “So this is part of ‘the life of a pilot,’ which is: You go into it with this great sense of camaraderie and boisterousness and youthful vigor, but the world will not tolerate it. And, eventually, you’ll be left with the knowledge of just how fragile life is.”

Watkins doesn’t end his class on this sobering note, but he does want it to sink in. After we walk back to his house, he pulls from a duffel bag World War I relics for me to inspect: a canteen insulated with beeswax, a primitive gas mask, and a stiff, heavy trench coat. Then he hands me a “trench club,” an 18-inch, wood-covered lead pipe with an egg-shaped ball at the end. It looks innocuous, but it has enough heft that I can imagine, with one swing, splitting an end table in two. Used full force in hand-to-hand combat, it’s a “terrible weapon,” Watkins acknowledges. Sharing these “tactile experiences” with students makes history “human,” he adds. “Otherwise, it just becomes too distant.”

And distance isn’t an option when working with high-school-age kids. In fact, Watkins teaches them for just that reason. “It’s something about that cusp, which I’ve found almost hypnotic,” he explains. “They have the enthusiasm of children and they have the capacity of adults. And it’s this incredibly mercurial time. ... It’s the time of the line from [writer Friedrich von] Schiller: ‘Keep true to the dreams of thy youth.’ This is when these dreams come about. And if you can be reminded of that on a daily basis, you cannot go home and listen to anybody’s voice but your own when push comes to shove. So they don’t know it, but they’re doing me an incredible favor.”

As for favors, Pat Clements, the 28-year Peddie veteran, says of the effect both Paul and Cath have on the school’s students: “Kids are in the business of inventing themselves, and you need adults with whom students work who can model the kinds of values and behaviors you want the kids to practice. They do that.”

There are times, however, when being a role model is especially challenging. In his books and classes, Watkins focuses on what he calls “hinge” periods, when the world is in turmoil, its fate uncertain. And on this Veterans Day, he found himself teaching about one war as another raged in the Middle East. Watkins, who served in the Eton College Officers’ Training Corps, is no pacifist; war is sometimes necessary, he says, “and when it is necessary, it needs to be executed with the utmost violence and finality. But I also”—noticing my tape recorder, he stops himself. Then, with a chuckle, he adds that he’s not going to comment on current events “with that thing on.”

But he already has. Earlier today, he told his World War I class that Europeans take Veterans Day seriously, honoring the dead at precisely 11 a.m. with three minutes of silence. “So this healing process, this grieving process, if you want to call it that, is a vast continuum,” he explained. “And it continues not only through those who lived through [the war] but through we who did not. And it is perhaps only through the grieving process that we come to some sort of realization about how to prevent it. The sad part is that we don’t; we do not prevent it.”

He told the students that by the time Thanksgiving rolls around, he wanted to make sure they’d discussed how it’s possible, after the “war to end all wars,” that another global conflagration followed by a handful of regional conflicts involving American troops could have taken place.

Sounding almost apologetic, he added: “There is something that I am not teaching you, that I myself have not been taught. There is something that is sort of vastly wrong, with either the teaching of history or the understanding of it, that continues this thing.”

He paused for a moment, the class hanging on his words, then quickly said, “OK, I had to say that; let’s package that away,” and resumed his lesson.