Reading First’s $1 billion-a-year investment in improving reading instruction seemed to be the kind of incentive that would push publishers to develop a new generation of products and approaches to match the research base the No Child Left Behind Act requires. But the money for instructional materials has not spread much beyond the handful of big publishing companies and name-brand programs that have dominated the market for years, according to industry reports and observers.

Nearly five years after the federal program was rolled out, it appears that the intended expansion of choices of core and supplemental materials hasn’t happened. In fact, some experts say, little has changed in the kinds of texts being offered, despite the potential many educators saw for Reading First to fuel a dramatic shift in how reading is taught in the nation’s schools.

“The distribution of rewards in Reading First followed familiar patterns,” said Marc Dean Millot, the founder of K-12Network.com, an Alexandria, Va.-based consulting firm that provides research and analysis on the school improvement industry. “The traditional providers of materials enjoyed the spoils, while the upstart firms [the federal law] favored were more or less frozen out.”

As a result, publishers that have long dominated the market—McGraw-Hill, Houghton Mifflin, and Harcourt—boast the most widely used core reading programs in Reading First schools, according to an interim implementation report released by the U.S. Department of Education earlier this year.

That fact has left many publishers, large and small, licking their wounds and reluctant to invest more in new and improved texts and supplemental materials. In anticipation of the new funds Reading First schools would have for materials, many curriculum companies had pumped money into scaling up their offerings and coaxed investors with the potential for profit, said Mr. Millot, a former senior social scientist for the Santa Monica, Calif.-based RAND Corp.

Some publishers undertook major revisions of their materials to incorporate the elements that research suggests are essential for effective reading instruction, and that Reading First requires.

“There was a great deal of enthusiasm that this would mean an expansion of the market,” said one publisher of a popular supplemental program for the early grades. He did not want to be identified for fear his criticism of the process would cost him more business. “We strengthened all those [required elements] in our program to be in better alignment to what the Reading First goals were and also to enhance our position in the marketplace.”

Instead, he said, the perceived preference by federal officials and grant reviewers for some commercial programs over others did “serious damage” to his family-run company.

Many publishers found they were unable to break into the Reading First market, and some couldn’t even sustain their existing business for K-3 reading materials, said Charlene Gaynor, the executive director of the Association of Educational Publishers, based in Logan Township, N.J. More than two dozen publishers in the trade organization—which primarily represents the supplemental and intervention materials market—sought to get their concerns on the record with federal investigators who audited the program this year, she said, though none was ever interviewed.

Oregon Origins

Almost from the start, Reading First—championed by President Bush as part of the No Child Left Behind school improvement law—was dogged by charges that federal officials and their representatives seemed to favor specific commercial programs and products, as well as consultants.

Those concerns prompted the educational publishers’ group and other publishers and associations to register repeated complaints with the Education Department. Those complaints—in particular, ones brought by the Baltimore-based Success for All Foundation and the Savannah, Ga.-based independent publisher Cindy Cupp—sparked federal investigations into the implementation of Reading First. (“Inspector General to Conduct Broad Audits of Reading First,” Nov. 9, 2005.)

Education Department Inspector General John P. Higgins Jr. has been conducting a broad review of the program over the past year in response to complaints that federal officials forced states to adopt or encourage the use of specific commercial products and consultants.

The first of six reports, released in September, offered a blistering critique of the federal department’s management of the program. (“Scathing Report Casts Cloud Over ‘Reading First’,” Oct. 4, 2006.)

Two other reports were critical of Wisconsin and New York officials’ oversight of their states’ grants. More reports are due out in the coming weeks, and a separate review by the Government Accountability Office, the congressional watchdog agency, is scheduled for release Jan. 19.

The perception of an “approved list” began with the Reading Leadership Academies, sponsored by then-U.S. Secretary of Education Rod Paige in early 2002 to guide state officials on the grant-application process. During those workshops, materials from several commercial reading texts and tests were held up as examples of the kinds that would be approved.

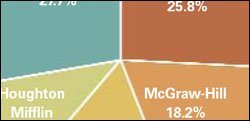

During 2005, four companies realized nearly three-quarters of the market on precollegiate instructional materials, including testing and technology, based on publisher revenue. The breakdown, which is for all subjects, has not changed significantly in recent years, according to Kathy Mickey, the managing editor of the education group Simba Information.

*Click image to see the full chart.

SOURCE: Simba Information

The Washington-based school division of the Association of American Publishers complained to Mr. Paige that the information provided by the Education Department suggested there was an approved list of programs that “may cause other program providers to refrain from materials development that would meet the needs of beginning readers even better.” Mr. Paige issued a statement clarifying that the department had not endorsed any particular materials.

But federal officials recommended that states use the “Consumer’s Guide to Evaluating Core Reading Programs” or require local grant recipients to do so. Use of the guide led to considerable consistency in the texts selected for participating schools. The guide, written by two researchers at the University of Oregon in Eugene, was incorporated into every state grant proposal.

Those researchers then offered assistance to a consortium of states—including Alabama, Idaho, Montana, and Washington—to establish common criteria to help state and local officials evaluate commercial programs.

The researchers, Edward J. Kame’enui and Deborah C. Simmons, also worked with the state of Oregon on its Reading First plan. The university sponsored a Web site for Oregon Reading First, for which staff members wrote ready-made reviews of the most widely used materials and posted them on the Internet.

Other states, frustrated by their own failures after having their Reading First grants sent back several times for revisions, began looking at successful plans, such as the ones in Washington state and Alabama, for clues to improving their own proposals.

An Education Week analysis of e-mail exchanges and other correspondence between the University of Oregon, officials in several states, and influential colleagues obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests found that the Oregon researchers sought to play a significant role in the selection of texts.

In September 2002, for example, Ms. Simmons asked her colleagues at the university via e-mail, and several state officials, for “wisdom on the topic of assisting states in program selection processes for Reading First.” Ms. Simmons wrote that the university could suggest states work together evaluating texts because it would be too costly for each state to do so independently.

Most states did not specify in their Reading First plans which texts grantees could use, but required them to review programs using the guide. That approach was deemed problematic by theOregon researchers.

“I have great concern about relying on [local grant recipients’] completed program reviews and proposed a second step of having an expert team provide a short list,” the e-mail from Ms. Simmons continued. “My thinking is that we could suggest coalitions across states.”

Mr. Kame’enui’s response suggested that researchers at Florida State University in Tallahassee also participate in the work, “which would help lead to a growing consensus across states about what good criteria are.”

A postscript to Mr. Kame’enui’s e-mail message suggested that “the feds will not support this activity—too politically sensitive.”

The list compiled by Washington state, and the reviews in Oregon, were shared or copied by many states and may have fueled perceptions that, because the Oregon experts had helped design Reading First, the lists of reading texts represented a federally approved list.

Mr. Kame’enui, who now serves as the director of the National Center for Special Education Research at the Education Department, went on to lead one of the regional Reading First technical-assistance centers. Another center is housed at Florida State. All three centers—the other is at the University of Texas at Austin—worked with states to implement Reading First.

Big Houses Out Front

Although dozens of commercial and home-grown core reading programs can be found in the nearly 6,000 elementary schools participating in the federal initiative, those put out by the largest publishers clearly dominate. The McGraw-Hill Cos.’ Open Court, Houghton Mifflin’s Nation’s Choice, and Harcourt’s Trophies are each used in at least 11 percent and as many as 23 percent of Reading First schools, according to the Education Department’s interim report on implementation.

In the overall K-12 market, Pearson Learning led with more than a 25 percent market share in 2005, followed by McGraw-Hill with 18 percent, according Simba Information. Harcourt garnered 17 percent that year, and Houghton Mifflin 11 percent, while other publishers shared 28 percent of the market.

That pattern of dominance seems to carry over into Reading First.

“At least on the surface, it appears that most of the dollars have gone to the larger publishing houses,” said Drew E. Crum, a senior analyst who follows educational publishing for Stifel Nicolas, a market-research and investment-banking firm based in Cleveland. “The notion of No Child Left Behind was to engender innovation and entrepreneurship, but from our vantage point that has not been the case.”

Those big publishers’ reading programs lead, however, because they started adapting reading research before the passage of Reading First, argues Maureen DiMarco, a senior vice president for educational and governmental affairs for the Boston-based Houghton Mifflin. And while some programs may look the same, they have changed significantly to reflect research on effective reading instruction, she said.

Ms. DiMarco, a former secretary of education in California, pointed out that the Golden State passed legislation in the mid-1990s that required textbooks with the kinds of skills-based lessons that are required by the federal law. The big publishers, she said, thus had experience meeting Reading First-style requirements and were in the best position to fill the need for instructional materials for participating schools.

“NCLB was not meant to be ‘go out there and experiment’ ” with new programs, Ms. DiMarco said, noting the cost of developing a core program—up to $100 million—makes it prohibitive for most publishers. “Reading First is about a core program, and that is what large publishers can do best.”

Many smaller companies have found their niche in the market for intervention programs, assessments, and teacher professional development, Ms. Gaynor of the Association of Educational Publishers said.

But Mr. Millot, the Virginia-based consultant, argues that if federal officials wanted to encourage reading programs closely aligned with research, they needed to set regulations that leveled the playing field for smaller publishers and rewarded them for tailoring their materials to the research.

“The big point is that the [Bush] administration established an audacious goal and did practically nothing to ensure its implementation,” he said. “It is enormously difficult for these small, innovative firms to crack into this market. You need breakthrough technology in order to meet the president’s goal, and the big companies are not going to come up with it.”