New York state officials are disputing a report that found extensive errors in how they awarded Reading First grants, maintaining that they administered the program the way the federal Education Department demanded.

“Many of the actions taken by [the New York state education department] were either explicitly delineated in the application that was approved by the [U.S. Department of Education] or recommended to NYSED by the [federal] contracted technical-assistance provider,” Commissioner of Education Richard P. Mills wrote to the federal department’s inspector general in response to the report his office released Nov. 3.

“Audit of New York State Education Department’s Reading First Program” is posted by the U.S. Department of Education’s inspector general.

The report is the latest in the inspector general’s broad investigation of the Reading First program.

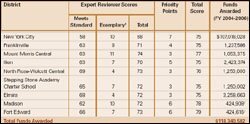

In the audit of New York’s Reading First plan, investigators conclude that the state erred in awarding grants to eight districts and a charter school that did not meet the minimum criteria for the program, and they recommend that the state return $118 million of the $216 million in federal money already awarded, the bulk of it to the New York City schools.

Some observers, however, are questioning the harshness of the findings in light of a previous report by the inspector general, released Sept. 22, that documented mistakes by the federal officials and consultants who had extensive input in the design and implementation of the state grants. (“Scathing Report Casts Cloud Over ‘Reading First’,” Oct. 4, 2006.)

The U.S. Department of Education inspector general’s report contends that the New York state education department awarded priority points to eight districts and a charter school only to bring their scores up to the 75 points needed to qualify for Reading First money, a claim the state agency disputes.

SOURCE: Inspector General’s Office, U.S. Department of Education

“The question is, ‘Is the U.S. department complicit in the way things were structured?’ It could be,” said Jack Jennings, the president of the Washington-based Center on Education Policy, which has studied Reading First since it started in 2002. “It’s like the states are getting whipsawed, in that first they follow what the department wants, then they are criticized for doing what they thought the department wanted.”

The report, the third such evaluation of the $1 billion-a-year federal reading initiative from the Education Department’s inspector general, concludes that New York officials should not have awarded Reading First grants to New York City, seven other districts, and a charter school. It also faults the state because it could not provide supporting evidence that any of the 66 districts participating in the program met all the requirements of the law.

State officials made numerous mistakes, according to the report, in evaluating local grant proposals for Reading First, a program under the No Child Left Behind Act that is intended to bring research-based reading instruction to struggling schools.

“Our work disclosed significant deficiencies in [the state education department’s] internal control for assuring and documenting that [local] applications met the Reading First requirements prior to awarding subgrants,” says the report, which was sent by Daniel P. Schultz, a regional inspector general.

‘A Rocky Start’

While New York officials received preliminary findings months ago, they were surprised the final report did not attach some responsibility for the mistakes to federal employees and consultants. “We felt that some kind of concern would be given to the state,” said Sheila Evans-Tranum, New York’s associate education commissioner, “as to the role that federal guidance played in this process. We were somewhat discouraged when that didn’t materialize in the final audit.”

Indeed, the confusion that states had early on in the program over the complex requirements and their difficulty in completing acceptable applications likely produced implementation problems, according to Gene Wilhoit, the new executive director of the Council of Chief State School Officers, based in Washington.

Mr. Wilhoit, who was Kentucky’s commissioner of education until last month, had complained to federal officials that the guidance his state received for the Reading First program went beyond what the law authorized, and that some of the federal consultants and reviewers assigned to his state had conflicts of interest as representatives or advocates of specific instructional approaches and commercial products.

Kentucky officials tried “in good faith,” he said, to draft a grant application that met the federal requirements as well as the needs of children and educators in his state. Even so, it took several months of intense negotiations before federal officials approved the state’s Reading First plan.

“It may be that some of the other problems with the negotiations and the contracts [at the federal level] related to what New York did,” Mr. Wilhoit said. “The state implementation had been done in the context of a rocky start and tough negotiations with the Education Department early on in the program. … I’m sure [New York officials] are going to try to represent that what they’d done is consistent with the guidance from the federal government and in line with what was negotiated.”

Federal education officials “intend to closely review the recommendations,” Chad Colby, a spokesman for the Department of Education, wrote in an e-mail last week. “In response, the secretary will take appropriate action both within the law and in the best interest of the students served by Reading First in New York.”

Documents Destroyed

In the case of the 1.1 million-student New York City district and the other districts cited, priority points were awarded improperly to bring them up to the minimal score, according to the inspector general. New York officials responded that priority points were awarded appropriately.

State officials could not provide the documents to explain why all the priority points were given, or supporting papers that any of the 66 grantee applications met federal requirements. The report says that critical documents had been destroyed or could not be located.

New York officials contend that the federal contractor, Learning Point Associates, advised them they could shred many of the reviewers’ notes. The Naperville, Ill.-based research group and professional-development provider disputes that claim, according to spokeswoman Ann Kinder. The Learning Point representative, Ms. Kinder said, advised state officials to follow their own record-retention policies.

Inspector General John P. Higgins Jr. has been conducting a broad review of the program over the past year in response to complaints that federal officials forced states to adopt or encourage the use of specific commercial products and consultants.

The first of six reports, released in September, offered a blistering critique of the federal Education Department’s management of the program.

Last month, an audit of Wisconsin’s Reading First program faulted state officials there for failing to hold all grantees to strict standards.

By itself, the New York report suggests significant mistakes by state education personnel. But some observers said the inspector general’s reports should not be read as separate documents, and together show how chaotic and confusing the implementation was at all levels.

“There is a series of reports coming out, … but each one is treated like a unique episode and not in the context of everything that’s already happened,” said Andrew J. Rotherham, a co-founder and director of the Washington think tank Education Sector and a former White House education adviser during the Clinton administration. “The chain of policy implementation went from Washington through the states, and had multiple choke points, meaning there were multiple places where things could go wrong.”

1st Grade Progress

Reading First serves 27,000 students in 49 public and 35 private schools in New York City.

Despite the findings, city officials say their program has proof it is having an effect. The percentage of pupils who met grade-level benchmarks for reading comprehension went up dramatically after the program was implemented, spokeswoman Lindsey Harr wrote in an e-mail. More than one-fourth of 1st graders in the city’s Reading First schools, for example, met the comprehension standard in the 2004-05 school year, compared with just 3 percent the previous year. Half the 1st graders demonstrated reading fluency that year, compared with about one-fourth a year earlier.

New York state officials plan to appeal some of the findings, and the recommendation to return the money, within the required 30 days, said Ms. Evans-Tranum, the associate commissioner.

“We felt that we had shown that we were not trying to do anything improper,” she said. “To be hit with this kind of dollar-amount giveback for doing what we were instructed to do seems a bit unfair.”