In the midst of an attempt by Arizona’s legislature and top education official to shut down ethnic-studies courses in the Tucson Unified School District, students here at Tucson High Magnet School are flocking to the courses this school year.

At least one class in two of the courses taught from a Mexican-American perspective at this school have more than 45 students, although the union contract calls for no more than 35 students in a class. School district officials say enrollment in Mexican-American studies in Tucson Unified’s 14 high schools has nearly doubled since last school year, from 781 to 1,400 students.

“Ethnic studies allow me to read and view and analyze different forms of literature and learning from another perspective,” said Krysta Diaz, 17, one of 386 students taking an ethnic-studies course at the school this year. The courses attract primarily students like Ms. Diaz, who are of Mexican-American heritage, but also draw in the occasional African-American, Anglo, or immigrant from a country other than Mexico.

Ethnic-Studies Courses Provide Different World View

Tucson High School students contest charges that ethnic-studies courses teach minority students that they are victims.

Some students say the controversy over ethnic studies caused them to want to check out the courses for themselves. But others say they signed up to learn more about social justice generally or Mexican-American culture and history specifically.

The political storm engulfing the debate over ethnic studies in Arizona’s high schools seems to be gaining a momentum like that of other recent high-profile debates in the Grand Canyon State, such as the one over its plans for enforcing federal immigration laws.

Fostering Hostility?

Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Horne and Deputy Superintendent Margaret Dugan contend the courses teach anti-American ideas and encourage Mexican-Americans to think of themselves as victims. In public letters, Mr. Horne has quoted a former teacher from Tucson Unified as saying the courses foster hostility among Mexican-American students toward U.S. society.

The state schools chief helped convince the Arizona legislature to approve a law, signed in April by Gov. Jan Brewer, a Republican, that aims to ban the kind of ethnic studies public schools are offering. Scheduled to take effect Dec. 31, the law bars all public schools across the state from providing courses designed for a particular ethnic group, that advocate ethnic solidarity, or that promote resentment toward a race or group of people. But public attention has focused on the 60,000-student Tucson district, known to have the only districtwide ethnic-studies program in the state, where a showdown is currently shaping up between state and district school officials.

Last month, Mr. Horne sent a letter to John Carroll, Tucson’s interim school superintendent, saying that if the district continues to teach ethnic studies after the law becomes effective, the Arizona education department will withhold 10 percent of the school district’s funds. Mr. Horne, who is the Republican nominee for state attorney general, won’t be in his education post then. But John Huppenthal, who landed the Republican nomination to replace him, has run a radio ad saying he aims to shut down the ethnic-studies courses, according to local news media.

A cut in funds “would sting,” said Abel Morado, the principal at Tucson High. But he said he believes the Tucson Unified school board will stand up for continuing to offer ethnic studies. The courses are valuable, he said, because “a student’s identification with the curriculum is non-negotiable.”

The expansion of ethnic studies in the Tucson school district is also a key component of a post-unitary status plan that stemmed from a federal desegregation case. The plan was adopted by the district’s school board in July 2009 and approved by a federal judge in December.

At the 2,900-student Tucson High Magnet School, where the ethnic-studies courses have been taught since 1998, students can earn regular English, American history, or American government credits for the courses. Teachers use regular textbooks as a point of reference, said Martin Sean Arce, the district’s director of Mexican-American studies, but also use sources such as Occupied America: A History of Chicanos, by Rodulfo Acuna, that teach perspectives that may not get much play in a traditional K-12 classroom. In a paper he co-wrote last year for an academic journal, Mr. Arce contends that the courses draw on “culture as a resource” and help students develop their own academic voice.

Broad Appeal

While critics have targeted the ethnic-studies courses with a Mexican-American emphasis, Tucson High Magnet also offers a Native-American literature and an African-American literature course under the same umbrella. Of the 386 students taking ethnic-studies classes at the high school, 332 are taking Mexican-American studies while 54 are taking either African-American or Native American studies. About 70 percent of the school’s students are Latinos, mostly Mexican-Americans; 20 percent are Anglos, and the rest are African-American, Asian-American, or Native American.

In his public letters, Mr. Horne quotes criticism of ethnic studies at Tucson Unified by John A. Ward, a Mexican-American and a former U.S. history teacher for the district, that a columnist for The Arizona Republic cited in 2008. Mr. Ward taught a class in American history from a Mexican-American perspective at Tucson High during the 2002-03 school year. He is now a school district auditor for the state auditor general.

Mr. Ward said in an interview this month that he shared the teaching of the class primarily with Mr. Arce though two other Mexican-American men also sometimes taught it. He said the other teachers aimed “to create this very, very strong ethnic identity among the kids that created a sense of separatism, that America was a country run by the white establishment, that they were outsiders to it and always would be, and that they had to come together as a unified group and fight the system.”

By contrast, said Mr. Ward, “if I had an ideological perspective, it was that while we fall short, the overall trajectory of this country has always been to make people [of all colors] freer. It’s still a work in progress, ... but we’re moving in the right direction.”

He said he fought to introduce works by conservatives to students to balance out their other assignments. He wanted to assign What’s So Great About America, by Dinesh D’Souza, and writings by former U.S. Supreme Court nominee Judge Robert Bork.

Mr. Arce said this month that he told Mr. Ward that such writings weren’t appropriate for the course. By both men’s accounts, Mr. Ward was removed from the course and reassigned to other teaching duties.

A central issue in the debate is how much academic freedom is afforded a school district over its curriculum.

Ten teachers in Tucson Unified School District’s Mexican-American studies department, plus Mr. Arce, intend to file a constitutional challenge to the state law banning ethnic studies in mid- to late October, according to Richard M. Martinez, a Tucson-based lawyer who is representing them. He said the lawsuit will be filed in U.S. District Court in Tucson.

Mr. Martinez said the challenge will argue that the state law violates the First and 14th amendments of the U.S. Constitution because it targets one school district, Tucson Unified, and one group of people, Mexican-Americans.

Administrators and teachers in the district acknowledged that the ethnic studies courses are not the traditional high school fare. But they said they are about teaching “empowerment,” not victimization.

Curtis Acosta, who teaches juniors and seniors Social Justice and Latino Literature at Tucson High Magnet, said courses such as his offered by the Mexican-American studies department provide “a classroom that is more authentic to the students’ lived experiences.”

On a recent school day, Mr. Acosta gave seniors homework to write a bibliography of eight books, songs, movies, “or other types of artistic expression that has either influenced your life or illustrates who you are as a person.” They were also instructed to write 80 to 150 words about “the reason the words resonate with you.”

The assignment came with a pep talk for students to be bold in demonstrating their academic ability. “People get into who we are, what we are,” Mr. Acosta said. “Maybe we’re not who they think we are.”

The students also worked in groups to reflect on an article about the origin and contribution of hip-hop music to the United States.

Real-Life Lesson

Meanwhile, for the American Government/Ethnic Studies course, teacher Maria Federico Brummer has designed a unit on the ethnic studies controversy. For a recent class, she assigned for homework a news article about the dispute, two opposing editorials in the debate, and one of Mr. Horne’s public letters criticizing ethnic studies. She didn’t express a point of view on the issue.

Students say that critics’ claims that they’re taught to be victims in the class couldn’t be further from the truth.

The difference between ethnic studies and regular high school courses, said Roman Figueroa, 17, is “we are more socially critical of a lot of things around us. We explore the other side of the story.”

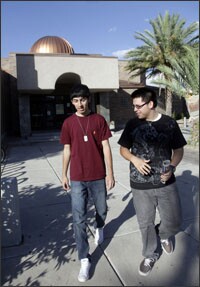

In a recent discussion in Mr. Acosta’s class, Mr. Figueroa said a more diverse group of students should be recruited to ethnic studies. He took a step toward that goal himself by persuading his best friend, Nasrat Malekzai, 18, to enroll in Latino literature. Mr. Malekzai is an immigrant from Russia and a member of Afghanistan’s Pashtun minority.

For his part, Mr. Malekzai said, he chose to enroll in Latino literature rather than regular senior English because he wanted to learn more about Mexican-American culture. After all, he said, he’s “surrounded” by Mexican-Americans at school. “The class has opened my eyes,” he said.