The San Antonio Independent School District can now put a laptop or tablet in the hands of every one of its almost 50,000 students—reaching a 1-to-1 computing environment years ahead of schedule due to the unprecedented rush to buy new tech brought on by coronavirus school closures.

But Ken Thompson, the district’s chief information technology officer, knows that securing new Chromebooks amid crushing demand from competing districts around the country and then distributing them to students in a rapid-fire process was just the beginning.

At some point in the future, whenever it’s deemed safe for school buildings to reopen, students will be returning those loaner devices. Then, the process starts to transition tens of thousands of brand-new laptops into devices intended to provide a digital boost to learning inside school buildings.

And that move will have big implications: Can the district’s new data center handle the demand? How is the district going to sanitize all those devices when turned in? And how will teachers need to be trained to integrate the devices into instruction in meaningful ways?

Another pressing technical matter: making sure every school has WiFi access throughout the building.

“Right now, my buildings are not fully lit up,” said Thompson. “Our goal is to be able to provide learning everywhere on a campus, from the gym to the cafeteria. We have to address that quickly before the devices come back.”

Those are key challenges for educators at all levels as many districts look toward the next school year with more mobile devices at their disposal and more lesson plans geared specifically toward teaching and learning with a laptop or tablet.

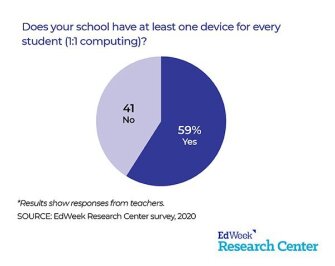

The prevalence of full 1-to-1 laptop programs hasn’t experienced a drastic shift since schools switched to distance learning amid the global pandemic, according to a new, nationally representative survey conducted by the EdWeek Research Center. Just 59 percent of teachers in early May said they had at least one device for every student, up only two percentage points from February before U.S. schools began to close.

But the COVID-19 school building closures that affected more than 55 million students this spring prompted many districts to buy laptops and tablets in what has been described as a never-before-seen pace and volume. Even if districts are not reaching 1-to-1 status, more of them are now armed with more mobile computers than ever before: Hundreds of thousands of devices—at a minimum—have been ordered in the last three months alone.

‘Golden Opportunity’

It’s the type of mass tech infusion that has the potential to reshape learning inside and outside the classroom, for better or worse. And that’s one of the pressing questions underlying the national remote learning experiment unfolding in real time: How will schools utilize this influx of new devices in ways that improve student learning?

“This is such a golden opportunity to transform teaching and learning into a more tech-based ecosystem,” said Leslie Wilson, the co-founder and former CEO of the One-to-One Institute, a nonprofit that consults with schools and districts. “But in the real world, you can’t just deploy devices and expect you’re going to transform education for the better simply because you’ve done that.”

In the San Antonio district, officials are hoping to recoup the $6.1 million cost of its acquisition of 30,000 laptops by floating a bond election in November. To reach 1-to-1 computing across all grade levels, the district purchased 30,000 laptops in mid-March to accompany 25,000 devices already on hand.

Patti Salzmann, the district’s chief academic officer, said some changes on the horizon to better accommodate the devices include likely acquiring a learning management system for the entire district. Currently, teachers are using Google Classroom as a central hub, and while free and convenient, Salzmann said the district can’t extract all the useful student data it needs from Google Classroom.

“We don’t know the quality of the interaction,” she said. “With an LMS, we can monitor information other than whether you logged in and what your grade is.”

Professional development will also be fine-tuned to incorporate digital learning more, she said. Teachers are already offered a “robust” digital program that includes tools such as Screencastify and NearPod, but Salzmann said “going forward there would be an emphasis on ensuring that is naturally integrated 100 percent into” training.

District-issued laptops will stay with students at least through the summer, so they can tap into different programs, including an online portal to interact with classmates and engage in academic exercises that will change weekly until the new school year starts. Once the laptops return to school, Salzmann said they’ll be used plenty, but there will be a balance between screen time and face-to-face interaction between student and teacher.

“The idea that children are coming to school and sitting on a computer all day isn’t something anybody wants either,” she said.

‘We Just Need More Time’

In Detroit, where the school district is receiving 50,000 tablet-style laptops with internet connectivity in June as a gift from a coalition of business leaders and nonprofits, the approach to incorporating those devices into every classroom is going to be much more “methodical,” said Superintendent Nikolai Vitti.

Many districts have made the mistake of rolling out digital devices to teachers and students without first thinking about how those devices should be used for meaningful learning and the tech infrastructure needed to support them. To prevent such mistakes, follow these steps:

- Make sure your district’s computer networks are fully prepared to support new devices. That could mean increasing bandwidth or access points in school buildings.

- To maximize what mobile devices can provide district officials from a data-mining perspective, consider investing in dashboards or software that track and provide metrics on student progress.

- A school district’s chief academic officer and chief technology officer should be in constant communication. This way there’s cohesiveness between tech purchases and classroom curriculum.

- Buying devices requires more than upfront money. Consider and project future budget costs appropriately for device maintenance and upgrades.

- Try leveraging ideas about device usage from a working group of district officials, principals, teachers, and even students that can provide continual input on what is and what is not working.

- Teacher training is paramount. Professional development must emphasize using tech tools that allow teachers and students to unlock the learning power of mobile devices. It is best if this training happens well in advance of a device rollout.

Vitti said some of his teachers are so far behind the digital teaching curve that it won’t be until the 2021-22 school year when district-wide curriculum plans are tailored specifically toward the fleet of new devices. And Vitti emphasized it’s not just the teachers who can use the extra time learning how to use the devices effectively: “I’m a little skeptical that all our students are comfortable in the space of online learning.”

“We just need more time. There’s so much happening now. Stress is high. Trauma is high,” he said, noting that Detroit has been a hot spot for COVID-19 cases and when in-person classes resume teachers are likely to be worried about exposure, let alone changing their entire teaching approach. “We’d have resistance only because we didn’t plan and train enough. This is more methodical, more strategic, and more sensitive to where our teaching staff is.”

When Vitti arrived three years ago at the Detroit public schools, a district where up to 90 percent of its roughly 51,000 students do not have access to a laptop or internet at home, there was just one device available in school for every six students. A cohesive plan for buying and using tech at schools did not exist.

Since then, Detroit has bought 30,000 laptops, Vitti said, and was on pace to be 1-to-1 at K-8 by the end of this school year. Moving forward, the idea, he said, was to start investing in laptops for high school students. But then coronavirus upended those plans, and the 50,000 new devices will bring the district to a complete 1-to-1 computing ratio much quicker.

Up until now, the district had used its laptops to mostly supplement core instruction for reading and math only. The devices were tied to carts. Once the new batch arrives in the summer, Vitti said, they will be the “property of the families, not ours” and students can use them as their main device at home.

Starting in the fall, every student will carry a laptop daily, but the district’s core curriculum won’t be integrated with the devices until the following school year. That’s when the district can start implementing a broader shift to incorporate tech tools such as digital textbooks and “give assignments through Schoology,” a learning management system, Vitti said.

Even though there’s a sense of urgency to roll the devices into the mix faster, waiting will enhance “buy in and implementation,” he said.

‘Spray and Pray’ Approach Doesn’t Work

Back about 20 years ago, when Wilson, the co-founder of the nonprofit One-to-One Institute, started evangelizing for the idea of putting a laptop in the hands of every student, she said superintendents and district officials were loath to spend money on technology for the classroom.

But as districts warmed to technology, Wilson said they started buying laptops with no idea how to effectively use them. She called it the “spray and pray” model: “They spray every kid some type of device and pray that some meaningful learning happens.”

That approach, for instance, was taken in the Los Angeles schools several years ago and resulted in a colossal failure and a huge waste of money and time.

To avoid that kind of mess, districts need to plan ahead before moving to 1-to-1, she said—everything from network infrastructure to device selection to finances for maintenance and upgrades to teacher training. Failing to do so, Wilson warns, will result in a “randomized roll out that can cause a myriad of problems.”

On the flipside of a 1-to-1 computing district, there are school districts still without enough devices for students to do tech-driven, remote learning. Those districts are relying on packets and worksheets, but that doesn’t necessarily mean students are falling behind, Wilson said.

Elizabeth Keren-Kolb, a clinical associate professor of education technology at the University of Michigan, agrees, saying that students in districts lacking devices aren’t in an ideal situation but can still make the most of what’s available without losing ground.

“Packets and workbooks aren’t necessarily less than digital devices. Half the applications online are just doing things from workbooks,” said Keren-Kolb, who is currently surveying K-12 teachers, parents, and students about their experiences with remote learning.

Helping ‘Students in Need’

Coming up with the cash to pay for new devices has been one of the biggest challenges. The school district in Detroit is able to accelerate its 1-to-1 ambitions based on a $23 million philanthropic gift. At the San Antonio Independent School District, officials are hoping to recoup the $6.1 million cost of its acquisition of 30,000 laptops by floating a bond election in November.

But in Pittsburgh, more than 7,000 of the district’s 23,000 students did not have access to a device when distance learning started in mid-April. So the district took to raising money online. About a month later, the shortage still was about 4,000 devices, said Ted Dwyer, the district’s chief accountability officer and interim CTO.

“This is not a 1-to-1 approach. If we can secure funds, we’re going to do that as soon as possible,” said Dwyer, noting that the district had purchased about 5,000 devices following school closures but was still waiting for the bulk of that order to arrive. “Right now, we are trying to get devices in the hands of students in need,” he said.

Aleesia Johnson, superintendent of the Indianapolis school district, said her district is planning to use federal stimulus money mostly to pay for 21,000 new devices and up to 9,000 WiFi hotspots that will bring the district up to a 1-to-1 computing ratio. But those devices won’t arrive until July, leaving the district short on tech tools for the time being. Johnson said IPS also resorted to online fundraising to help cover some device and hotspot costs.

“When I look at Twitter or what I hear from calls with other superintendents,” she said, “it’s clear folks are trying to leverage community resources or any resources possible to any extent to pay for devices.”