The Wake County school district in North Carolina was in the process of a gradual, deliberate transition to 1-to-1 computing in early 2020, with the goal of a single device for every student in two years.

Then, the pandemic hit. Students were sent home for remote instruction. Suddenly, it became imperative that every kid in the district who needed a device to learn had one. Right away.

That meant buying a lot of new devices and handing them out quickly. When all was said and done, the district ended up spending about $48 million on new devices. The quick pace meant some devices were initially distributed without clear documentation of who they went to. The district revamped its record-keeping process.

“It felt, at times, a little bit like a fire sale,” said Marlo Gaddis, the district’s chief technology officer. “Sometimes, we weren’t perfect. I don’t think there’s a district in this country that could say they’ve done it perfectly.”

Even though the district was already planning to become 1-to-1, this isn’t how Gaddis wanted it to happen. The district lost “the ability to put the toothpaste back in the tube,” she said, meaning make tweaks or change direction at different points in the process.

The whole pandemic has been like a big proof of concept for 1-to-1. Now it’s taking all of those learnings and putting them into [practice]. What does 2021-22 look like?

Wake County is not alone.

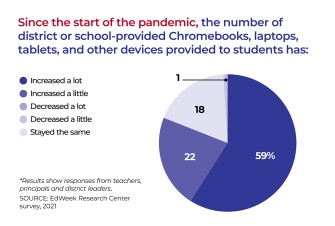

A survey last month of educators by the EdWeek Research Center found that about two-thirds recalled there was one school-issued device for every middle and high school student before the pandemic. Another 42 percent said the same about elementary school kids.

In the same survey, 90 percent of educators said there was at least one device for every middle and high schooler by March of 2021. An additional 84 percent said the same about elementary school students.

That dramatic change is sure to impact teaching, learning, district operations, and school budgets long beyond the pandemic. Districts that purchased devices for most students will have to decide if they want to stay 1-to-1 for the long haul. If so, they will have to continue to repair and replace devices, which creates ongoing costs. Teachers are also likely to shift their approach to instruction to incorporate the sudden windfall of new learning tools, which could put greater pressure on school districts to provide better professional development on how to effectively integrate the devices into learning.

“What most school districts did was they dropped everything, and they bought things whether they had budget for it or not,” said Keith Krueger, the CEO of the Consortium for School Networking. Many used one-time federal funds to cover the cost, he added: “An awful lot of stuff has been purchased and will be purchased over the coming months. That is good news in addressing an emergency situation, and a long-term challenge when you think of the total cost of ownership.”

If districts want to keep their new 1-to-1 device-to-student ratio long-term, “you have to have a plan for how you’re going to replace them. [Some devices] may have been not intended to be going back and forth between the school and home,” Krueger said.

And then there is a big fairness question question: Should districts even ask for devices back if a family doesn’t have one of its own?

Urgent action item was getting devices to students for at-home learning

A year ago, getting devices in the hands of kids, especially those who did not have access to one at home or had to share one with siblings and parents, became an urgent action item for many districts. In fact, 74 percent of educators surveyed by the EdWeek Research Center said their districts had invested “a lot” in devices since the pandemic started, with nearly another quarter saying their district had invested at least “some” money.

Another 87 percent of educators expected their districts to invest “some” or “a lot” in new devices during the 2021-22 school year. And 42 percent of educators said their district had purchased devices for every student.

Districts also had the challenge of figuring out which students needed devices the most. Nearly half of educators—47 percent—said their districts purchased devices for kids that didn’t already have one issued by the school system, while 46 percent focused on students at certain grade levels.

Another third said their districts provided devices to students who didn’t have access to a device at home. Sixteen percent said their districts bought devices for low-income students, while 17 percent said their districts purchased devices for kids in special education.

At some point in the pandemic, Wake County realized it needed to have a nuanced take on what it meant for a student to “need” a device, Gaddis said.

Some kids literally had no computer or tablet in the house that would allow the student to learn online. Others might be in families, all sharing one device. Still others might be families who felt most comfortable if their child’s technology had the district’s stamp of approval.

“I think everybody has struggled in the pandemic in terms of what ‘need’ is,” Gaddis said.

Schools weigh whether to continue offering 1-to-1 computing

Other districts that bought new devices weren’t necessarily planning to go 1-to-1. They will now have to figure out whether to continue the practice, and what that would mean for teaching and learning.

Before the pandemic, the Beaverton school district near Portland, Ore., used technology as a teaching tool, but 1-to-1 computing was not a signature feature of its classrooms, said Steve Langford, the chief information officer.

Elementary schoolers, for instance, had access to iPads, but not one device for every student. Instead, kids used the devices to collaborate in small groups or for academic intervention or enrichment. At the middle and high schools, each student had their own device they could take home with them. But teachers didn’t use the devices—Chromebooks—for every lesson.

“It was never this all-day, always online vision,” Langford said. “It was more how does technology accelerate some learning and provide some new opportunities for engagement. Once COVID happened, we had to quickly say, ‘OK, now we’re going to be interacting through a screen and that’s going to be true for an 18-year-old and a 5-year-old.”

The abrupt shift has created some new logistical headaches. For instance, Beaverton found that it needed some Spanish-speaking technical-support staff, to help parents when their kids’ district-issued devices malfunctioned. The creative solution: The district trained a handful of bus drivers and other support staff to serve as bilingual help desk staff. All of them are fluent in Spanish and English and were already receiving pay even though they weren’t actively transporting students.

The district, though, isn’t convinced it will continue with a heavy emphasis on 1-to-1 computing once students return to school buildings full time. “We are wrestling with that right now,” Langford said. “If our future is that kids K-12 are going to take home devices, then we need to make some decisions and preparations right now,” including how to fund the continued use of the devices.

More than a third of the district’s 18,000 iPads were bought at least six years ago and are near the end of their usable life. If Beaverton is going to continue supporting 1-to-1 computing, those iPads will need to be replaced.

Plus, teachers will need further professional development on the best instructional approaches for 1-to-1 computing environments, and parent concerns about their children having too much screen time will need to be addressed.

“There’s instructional impact, there’s operational impact, and then there’s financial impact to those decisions,” Langford said.

Nearly a third of district leaders—31 percent—reported that they ordered new devices during the pandemic but some of their purchases still have not arrived, as late as March 2021, according to the EdWeek Research Center survey.

You'd call and ask where an order was, and you could hear them shrug their shoulders over the phone.

“You name a piece of hardware and we had delays across the board,” said John McAtee, the technology specialist for the Pleasantdale School District 107 in Burr Ridge, Ill., near Chicago. “You’d call and ask where an order was, and you could hear them shrug their shoulders over the phone.”

The Herkimer Central School District in central New York state simply gave up when Chromebooks that were supposed to be delivered in September didn’t arrive by February, said Ryan Orilio, the director of technology and innovation. The district wound up canceling some orders.

So instead of buying something new, Orilio’s district opted to extend the life of devices that it was planning to replace.

“We were able to repurpose some older devices,” Orilio said. “We really just changed the plan on our replacement cycle at least for this year.”

Taking back devices that were given to students during the pandemic

Now that devices have been handed out, they may need to come back, especially if the district isn’t planning to immediately move to a 1-to-1 computing model.

For instance, the Livonia school district in Michigan provided 8,000 devices to students who didn’t have them at home. That was more than half the district’s total enrollment. The district isn’t sure if it will move to a 1-to-1 model, so Tim Klan, the administrator of information and instructional technology, is anticipating taking back many of the devices at some point.

“We are going to take them back, the question is when,” he said. Once the district collects the devices, it will need to test and clean them, particularly since some of the devices look like they’ve spent the pandemic “on the floor mat of somebody’s car.”

The district is currently doing in-person learning, but sends students home with the devices an hour earlier than it did before the pandemic. Students are expected to spend the extra time doing schoolwork, in a sort of at-home study hall.

Students have gotten accustomed to having a device at home, and that could be a challenge for the district. “I feel like we’ll get a lot of pushback,” when we take them back, Klan said. “They’re used to having them, they like having them.”

Despite the uncertainty and challenges, it appears that many districts who invested devices during the pandemic will at least explore continuing to support 1-to-1 computing environments for their students.

“The whole pandemic had been like a big proof of concept for 1-to-1,” said Gaddis of Wake County. “Now it’s taking all of those learnings and putting them into [practice]. What does 2021-22 look like?”